That which gave the most pleasure and ornament to the city of Athens, and the greatest admiration and even astonishment to all strangers, and that which is now Greece’s only evidence that the power she boasts of and her ancient wealth are no romance or idle story, was Pericles’ construction of the public and sacred buildings.

Now that the city was sufficiently provided and stored with all things necessary for the war, Pericles said they should convert the surplus of its wealth to such undertakings as would hereafter, when completed, give them eternal honor, and for the present, while in process, freely supply all the inhabitants with plenty. With their variety of workmanship and of occasions for service, which summon all arts and trades and require all hands to be employed about them, they do actually put the whole city, in a manner, into state pay—while at the same time she is both beautiful and maintained by herself. For as those who are of age and strength for war are provided for and maintained in the armaments abroad by their pay out of the public stock, so, it being his desire and design that the undisciplined mechanic multitude that stayed at home should not go without their share of public salaries—and yet should not have them given them for sitting still and doing nothing—to that end he thought fit to bring in among them, with the approbation of the people, these vast projects of buildings and designs of work that would be of some continuance before they were finished and would give employment to numerous arts, so that the part of the people that stayed at home might, no less than those that were at sea or in garrisons or on expeditions, have a fair and just occasion of receiving the benefit and having their share of the public moneys.

The materials were stone, brass, ivory, gold, ebony, cypress wood; and the arts or trades that wrought and fashioned them were smiths and carpenters, molders, founders and braziers, stonecutters, dyers, goldsmiths, ivory workers, painters, embroiderers, turners. Those again that conveyed them to the town for use, merchants and mariners and shipmasters by sea, and by land cartwrights, cattle breeders, waggoners, rope makers, flax workers, shoemakers and leather dressers, road makers, miners. And every trade in the same nature, as a captain in an army has his particular company of soldiers under him, had its own hired company of journeymen and laborers belonging to it banded together as in array, to be as it were the instrument and body for the performance of the service. Thus, to say all in a word, the occasions and services of these public works distributed plenty through every age and condition.

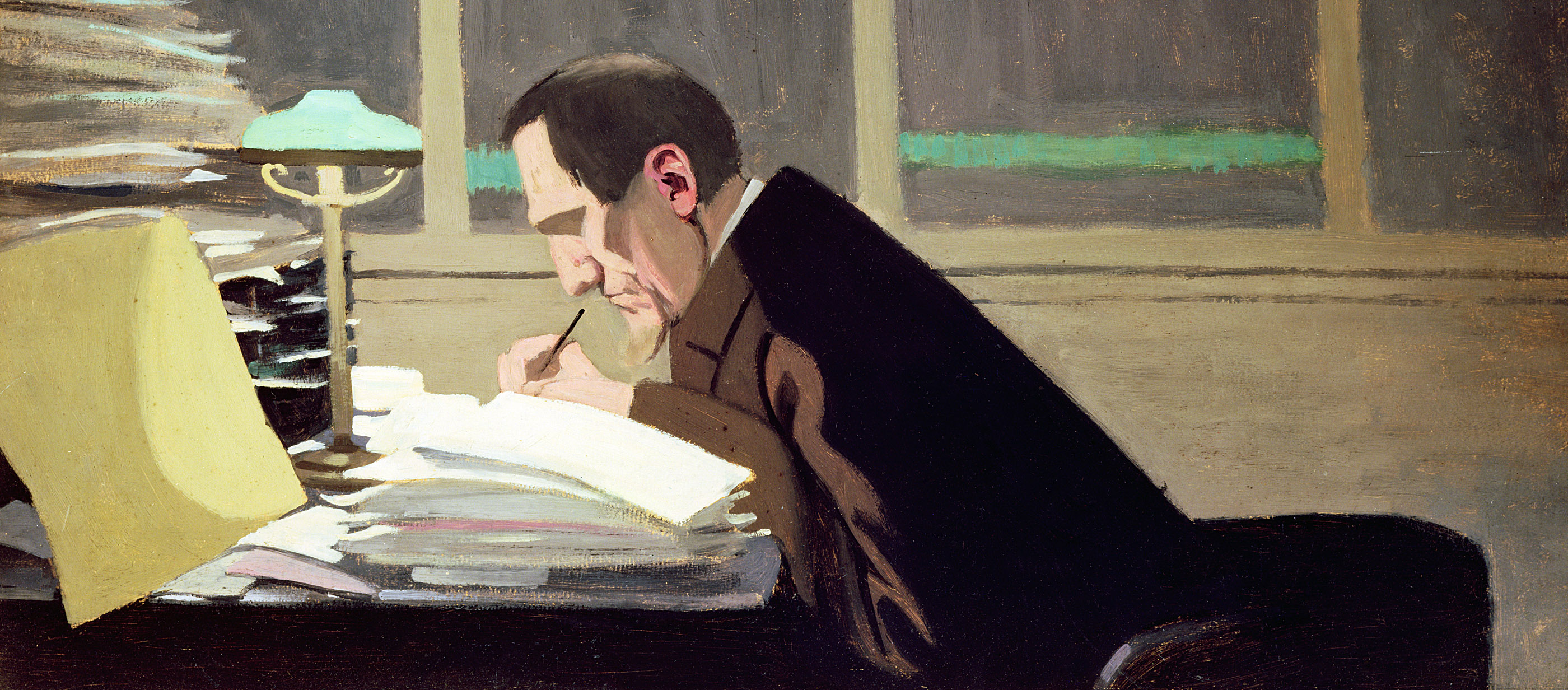

Félix Fénéon working at the French literary journal La Revue Blanche, by Félix Vallotton, 1896.

As then grew the works up, no less stately in size than exquisite in form, the workmen striving to outvie the material and the design with the beauty of their workmanship, yet the most wonderful thing of all was the rapidity of their execution.

Undertakings, any one of which singly might have required, they thought, for their completion, several successions and ages of men, were every one of them accomplished in the height and prime of one man’s political service. Although they say, too, that the painter Zeuxis once, having heard Agatharchus the painter boast of dispatching his work with speed and ease, replied, “I take a long time.” For ease and speed in doing a thing do not give the work lasting solidity or exactness of beauty; the expenditure of time allowed to a man’s pains beforehand for the production of a thing is repaid by way of interest with a vital force for the preservation when once produced. For which reason Pericles’ works are especially admired, as having been made quickly, to last long. For every particular piece of his work was immediately, even at that time, for its beauty and elegance, antique; and yet in its vigor and freshness looks to this day as if it were just executed. There is a sort of bloom of newness upon those works of his, preserving them from the touch of time, as if they had some perennial spirit and undying vitality mingled in the composition of them.

From Parallel Lives. More than three deacdes after the polis had been razed by the Persians, Pericles began a series of public works, among them the Parthenon, the gateway to the Acropolis, and the Odeon. Plutarch’s book of paired biographies of Greek and Roman heroes was translated into English by Thomas North in 1579, becoming a major source for several of Shakespeare’s plays, among them Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra.

Back to Issue