I imagine that one of the first forms of behavior, like one of the first signals, may be reduced to this: “Keep me warm.”

—Michel Serres, 1982Living Land

Peat, pray, love.

In nearly all civilized countries, man, after having destroyed the forests, has sought under the earth for means of warming himself. He lives on an investment of ancient vegetation, which the wise foresight of nature laid by for his wants. Coal, anthracite, and peat, according to the different geological countries, compensate for the absence of wood, which is becoming more and more rare. Peat beds are distributed over several regions of Europe. They are found in England, France, Germany, Switzerland, and even in Italy; but nowhere are they so abundant as in the Netherlands, which may be called the country of peat. Here, in fact, it is not rare to find beneath a layer of clay or sand that black and bituminous earth which the inhabitants employ as fuel. In digging canals or laying the foundations of houses, veins of this combustible that have been buried for centuries are daily laid bare. A few feet from the surface, the peat makes its appearance, and at some spots it reveals itself by the inconsistent nature of the soil. The elastic, water-swollen earth yields under the foot that presses it and then rises again. This quivering, sensitive soil is known to the inhabitants, who say of it, Het land leeft—the land is alive.

The extraction of peat supplies labor for thousands of arms. Nearly the whole population of Holland warms itself with the earth—but how many live by it! The mode of warming is akin to the manners and domestic life of nations; a friend of Walter Scott’s told us that he had often heard the celebrated romancer repeat, “Tell me how a nation warms itself, and I will tell you what it is.” The ancients thoroughly comprehended these relations, for they made the hearth the religious symbol of the family. With admirable good sense, they placed the gods in that part of the house around which the tenderest affections of the human heart are concentrated.

In Holland, that country where everything is peculiar, the fuel could not resemble that of other nations. Virgil, that great painter of rustic manners, has noticed how much there is interesting and poetical in the smoke that rises toward evening from a cabin. In the Netherlands, the chimneys smoke more than elsewhere. How often have I stopped on the interminable plains of Drenthe and Overijssel to watch the thick white clouds that a modest peat fire sent skyward! These clay or turf roofs, thus draped, caused me to dream of all the tranquil joys of nature; for the smoke that rises at eventide to heaven may be called the prayer of the house.

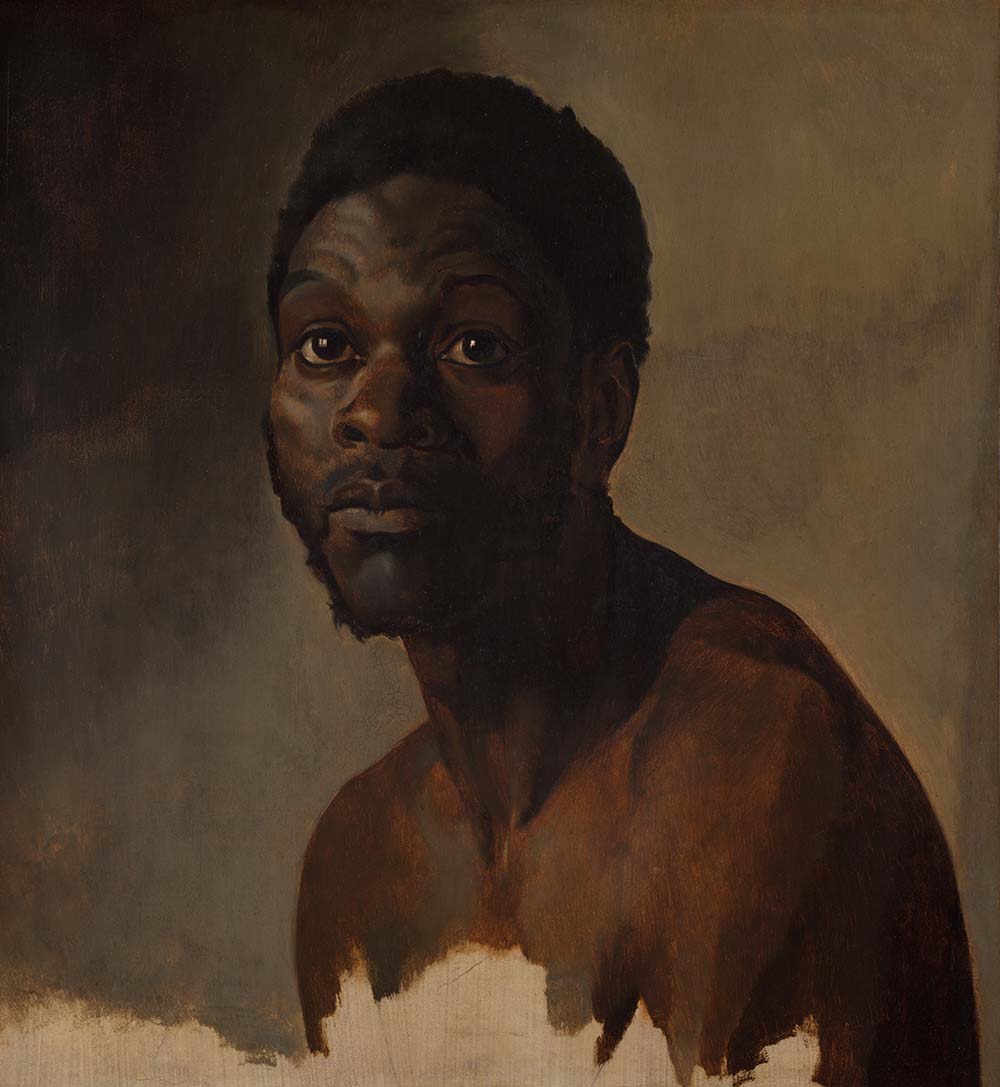

Bust-Length Study of a Man, by François-Auguste Biard, 1848. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, Wolfe Fund and Wheelock Whitney III Gift, 2022.

Peat is not a substance created from the origin of things and immutable, nor is it preexistent: it was not made, but made itself. This land is formed and composed even at the present day before our eyes. As peat is a land that grows, this very growth has been variously explained. Some visionaries have referred the formation of the peat beds to the influence of the planets. The relations of the worlds to one another are not known to us. In the present state of science, it is as imprudent to affirm these relations as to deny them; but, at any rate, there is no reason why the light of the heavenly bodies should act more on the peat than on the other strata of the earth.

In the province of Overijssel, not far from Almelo, there is a wood (the wood of the Drieschigt) in which I saw, so to speak, the peat forming under the naked eye. Half copse, half peat bed, this melancholy wood constitutes a new genesis—the genesis of the present phenomena of creation. The limit between a part of the vegetation that is decaying; the passage of the living wood into the peat stage; the different phases of this more or less rapid operation; the labor of the slow chemical agencies by which vegetable matter is transformed into a species of growing land—all this justifies the idea of the ancient peoples, who placed in the forests of Gaul and Germany the sole worship worthy of divinity.

The natural history of this metamorphosis demands our attention. Some botanists have remarked recently on a relation between certain large trees and low plants, which grow on the surface of the ground. The antagonism between these two systems of vegetation is speedily declared. With time the heaths and mosses devour the forest; the beech-tree is conquered by the blade of grass. The natural formation of peat is allied to this continuous development of heather and moss. These plants die annually, but in dying they deposit their vengeance on the soil, if we may employ the expression. The mechanism by virtue of which the vegetable matter acquires the proportions of peat is remarkably simple and ingenious. The lower ends of the stem are annually detached from the dying shoots, and their fall gives rise to a peculiar mold. This layer, formed of vegetable detritus, rises slowly, while the moss continues to grow upward. Time gradually develops these inexhaustible fecundities of life and death. Vegetable generations are thus piled up on generations, spoils on spoils. The forest, half wood, half peat, then offers the image of those Egyptian catacombs in which the living grew on the dead. The great trees send down their roots into those gloomy galleries, where the ancestors of the vegetation, accumulated strata on strata, repose. This period of the growth of the peat marks more and more the period of the decrease of the wood. The peat that is attached to the forest, like the mistletoe to the oak, gnaws at it silently. Choked by the heath and mosses that swarm at their feet, undermined by the peat that they daily increase with their ruins, the great trees fall. When the trees have disappeared, the heath and mosses continue on the surface of the peat beds the slow, silent work of decomposition, which must necessarily augment the mass of combustible matter. In the midst of these empty plains, whence the primitive inhabitants (that is to say, the oaks, beeches, and firs) have disappeared in turn, man undergoes an indefinable feeling. His mind is elevated by the sight of the economic system of nature, which makes everything contribute to the utility of man, even to the quivering of the blade of grass that the wind detaches from the stem and that falls preciously into the darkness of the peat bed.

Alphonse Esquiros

In 1851 Alphonse Esquiros, a Romantic novelist and newly elected socialist member of the National Assembly, was expelled from France for opposing Napoleon III. During his nearly two decades in exile, Esquiros reported on Belgian, Dutch, and English society for the magazine Revue des deux mondes.