2021

2021

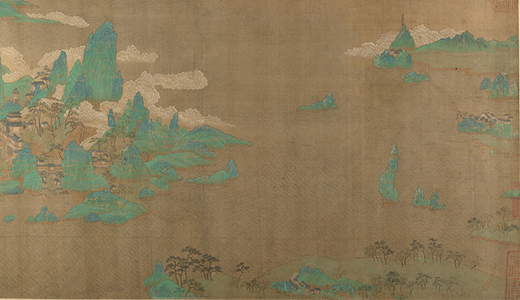

Sea and Sky at Sunrise, seventeenth century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, H.O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer, 1929.

On August 21—International Homeless Animals Day—a fishing boat arriving from China was intercepted a few miles from the coast of Taiwan. Local authorities asked the boat to wait at Kaohsiung Port, where the crew was tested for Covid-19. The Coastal Guard—which had been previously tipped off—found out later that the boat was carrying 154 cats held in sixty-two cages. The cats were being smuggled from China to be eventually sold on the Taiwanese market. According to The Guardian, the cats’ estimated value was $10 million TWD (U.S. $357,504). That Saturday night, the Bureau of Animal and Plant Health Inspection and Quarantine faced a difficult decision. The China’s Central News Agency reported:

As the origin of the cats was unknown, they were euthanized Saturday to prevent the import of infectious diseases that may threaten the health of other animals and humans in the nation, the BAPHIQ said.

In President Tsai’s comment on the issue, she said she was saddened by the incident, but she asked the public to understand that the BAPHIQ had to euthanize the cats to prevent the importation of infectious diseases, in accordance with the country’s laws.

c.

1738

c.

1738

Workers’ Demonstration, Paris, by Frères Séeberger, c. 1909. Rijksmuseum.

In the late 1730s Nicolas Contat was an apprentice at a printing shop in rue Saint-Sèverin in Paris. The working conditions at the shop were terrible, described in a fictional account he published in 1762. Apprentices were given rotten food, and it was hard to sleep, thanks to the noise of cats wandering around the house at night. One raucous evening, an apprentice decided to climb on the roof and mimic the howls of the cats near the master and mistress’ bedroom window. After a few insomniac nights, the master asked the apprentices to get rid of the cats—except the mistress’ pet, la Grise. The employees staged a fake trial and then violently killed the cats with their printing tools. They did not spare la Grise, laughing about it for days while the mistress mourned. Historian Robert Darnton, who analyzed the event in The Great Cat Massacre and Other Episodes in French Cultural History, wrote:

By executing the cats with such elaborate ceremony, they condemned the house and declared the bourgeois guilty—guilty of overworking and underfeeding his apprentices, guilty of living in luxury while his journeymen did all the work, guilty of withdrawing from the shop and swamping it with alloués instead of laboring and eating with the men, as masters were said to have done a generation or two earlier, or in the primitive “republic” that existed at the beginning of the printing industry. The guilt extended from the boss to the house to the whole system. Perhaps in trying, confessing, and hanging a collection of half-dead cats, the workers meant to ridicule the entire legal and social order.